The Lighthouse Partnership - Sailing Towards Success

- Malcolm De Leo

- Sep 1, 2025

- 36 min read

Whether you’re starting a company, working for yourself, building inside a startup, or even buried deep in a corporate giant, the job is the same: grow the business. There are a hundred ways to do it—you can optimize, cut costs, launch new products, expand into new verticals, or even buy your way into growth. But no matter which path you choose, one truth always holds: you’ll need partners to make it happen.

And yet, too often, partnership gets reduced to a transaction. Sign a deal, check the box, move on. Anyone who has actually had to rely on another company to drive their own growth knows it’s never that simple. Partnerships are messy. They’re nuanced. And when done right, they’re transformative.

That’s why in this post I want to dig into a few rules of thumb for thinking about partnerships—not as one-off deals, but as strategic levers for growth. And at the center of it all is one of the most powerful (and most misunderstood) concepts: the lighthouse partnership.

First, Let's Define the Lighthouse Partnership How do we define a "lighthouse partnership"?

Lighthouse partners are more than just partners. They do two things. First, they are a beacon of light in what can feel like a dark world of getting an idea off the ground. They shine a light forward by bringing the in-market data you need to make progress. Second, they are also a real, paying customer. Their adoption validates what you are building. Like a lighthouse, they show the way—for you and for others who might follow.

The metaphor works because lighthouse partners bring:

Visibility – Ships at sea look for the light. A strong lighthouse partner gives you outsized visibility in the market.

Guidance – Just like sailors steer toward the beam, other customers, investors, or partners use your lighthouse as validation of your legitimacy.

Safety – Lighthouses mean “safe harbor.” A credible lighthouse partner signals that your idea has merit and is worth believing in.

Momentum – One lighthouse pulls in others. Success begets success, and a lighthouse partner helps expand and further validate your business.

Why Talk About Partnerships?

Because too often “partnership” is a buzzword tossed around in pitch decks like confetti. Founders say it, big companies say it, everyone claims to be “partnering” with someone. But here’s the truth: if you think a partner exists only to serve your business, you’ve already missed the point. Real partnering isn’t one-sided. It’s not a shortcut to growth or a clever PR headline. It’s a decision to play a bigger game than you could on your own.

Partnership, when it’s real, means doing things that don’t always make immediate sense on a spreadsheet. It means giving loyalty where you technically don’t have to. It means going out on a limb not just for your team, but for someone else’s too. It’s the recognition that the sum of two groups working together can be greater than anything either could build in isolation.

After 30 years in business, I’ve seen two types of people: those who get this, and those who don’t. The ones who get it understand that sometimes you need help. And to ask for that help, you need both the confidence to own what you know and the humility to admit what you don’t. Maybe your organization lacks expertise, resources, funding, or leadership in a specific moment. Owning that truth is not weakness—it’s the bravery that drives innovation and growth. But partnering also requires trust, which is exactly why it makes people nervous. Trust feels risky. It forces you to let go of the illusion of control.

Here’s the funny thing, though: people often assume it’s just startups and scrappy small companies that need partners. Not true. Even the biggest global giants, with their endless resources, have to make the choice between “make, buy, or partner.” Buying can be clean and simple. Making everything yourself is usually a fantasy. Which leaves partnering—the option that creates leverage. And in today’s world, where tech moves at warp speed and no one can keep up alone, that option isn’t just nice to have. It’s survival.

A Warning to the Curious

A quick warning: partnering is full of nuance, and no post can capture every angle or hidden variable. What follows isn’t a manual—it’s a set of models and lessons meant to spark ideas, help you think differently, and maybe give you a better shot when you face your own partnering moments.

What’s Important, What’s Obvious, and What’s NOT Important

Before we go deeper into Lighthouse Partnerships and startups, I want to slow down and unpack something that often gets overlooked. In every partnership I’ve been part of, there are three different categories of things that show up: what’s important, what’s obvious, and what’s not important (even though people often treat it like it is).

It might feel odd to call this out, but after watching good partnerships thrive and bad ones implode, I can tell you that not knowing the difference between these three is where people get burned. The “important” things don’t always look urgent. The “obvious” things don’t move the needle nearly as much as people think. And the “not important” things? Well, those are the ones that can drag you straight into the ditch if you let them.

What’s IMPORTANT?

There are three things I’ve seen make or break lighthouse partnerships. They may seem soft or even squishy compared to spreadsheets and KPIs, but they’re the bedrock. Without them, nothing else holds.

Self-Awareness

This is where most founders and executives miss the boat. They see a potential partnership and think, “well, the business case is clear, it’s obvious we should do this,” and they just charge ahead. But self-awareness forces you to stop and ask: is this actually the right fit for us? It’s about being honest with yourself and your team—what you bring to the table, who is involved, where your blind spots are. And it’s also about being aware of what your partner brings—not just their assets, but their limitations, their quirks, and the hidden politics in their organization. If you skip this step, you’re not building on rock, you’re building on sand.

Honesty

Self-awareness only works if you put it into play through honesty. That means sizing up your partner honestly, but also communicating openly and clearly about your own motives, goals, and constraints. It means setting expectations you can actually meet, not ones you think sound good in the room. Honesty is the antidote to the passive-aggressive nonsense that kills partnerships. Think of it as self-awareness in motion, expressed through clear words and real conversations. You don’t need to overshare every detail, but you do need to put the real cards on the table and stop pretending the game is different than it is.

Trust

When self-awareness meets honesty, you get trust. And trust is the fuel line in the engine. It’s not a nice-to-have, it’s the thing that determines if you’ll get out of the harbor or break down before you leave the dock. The funny part is everyone nods their head when you say “trust is important,” but very few people actually build it into their operating principles. If you want your lighthouse partnership to weather storms, you have to put trust first. When you do, you’ll win more often than you lose—not because it’s a magic guarantee, but because you’ll avoid the quiet rot that eats most partnerships from the inside out.

What’s OBVIOUS?

Now, let’s talk about the obvious stuff. These are the things that everyone brings up in every partnership conversation, and sure, they matter—but they’re table stakes. They’re not where success is decided.

Metrics and Measures

Without fail, the first thing someone says in a kickoff meeting is, “how are we going to measure this?” And yes, metrics are important. You can’t manage what you can’t measure. But if you’ve ever been through a real partnership, you know the spreadsheet never tells the full story. You can track ROI, you can build dashboards, you can watch the KPIs rise and fall—but the moments that really define success, the “near-death” experiences and scrappy pivots that save the whole thing, those never show up in a cell. Metrics matter, but only in the obvious sense: they’re part of the system, not the heart of it.

Results

Of course you need results. If a partnership isn’t producing something tangible—growth, reach, revenue, whatever—then it’s not a partnership, it’s a hobby. But I put this in the “obvious” category because saying “results matter” is like saying “gravity exists.” It’s true, but it doesn’t tell you how to fly. Just because you write down the results you expect doesn’t mean you’ll achieve them. Partnerships succeed because people are willing to do the hard work that gets to results, not because the results are posted on a slide.

Collaboration

You can’t have a partnership without collaboration. That’s obvious. You have to work together, you have to align, you have to stay in the same boat rowing in the same direction. But here’s the trick: just saying “we’ll collaborate” doesn’t make it happen. People overvalue this one because they assume that if collaboration is mentioned, it will exist. The truth is, collaboration is obvious, but not sufficient. It’s the baseline condition, not the success factor.

What’s NOT IMPORTANT?

And now we come to the dangerous stuff: the things people think matter but actually don’t. These are the red herrings, the distractions that seem noble or strategic, but in reality only corrode the relationship.

Personal Interests

Let’s be blunt: partnerships aren’t about you. They aren’t about your ego, your career trajectory, or how much credit you get. Yes, how you conduct yourself and how you lead matter, but the second you make it about your own advancement, the partnership starts to tilt off its axis. A great partnership leader is a conduit, not the hero. You facilitate the work, you guide the process, you protect the true north: creating shared value neither side could have built alone. If you’re in it for the spotlight, you’ll suffocate the partnership before it gets off the ground.

Winning

Walk into a partnership with a hyper-competitive, “I’m going to win” mindset, and you’ve already lost. The rising tide lifts all boats—that’s the principle of partnering. Winning at your partner’s expense isn’t winning at all, it’s losing in slow motion. And yet, so many people approach partnerships like they’re some kind of zero-sum game. If that’s your mindset, stick to solo projects, because collaboration will eat you alive.

Corporate Loyalty

This one always shocks people when I say it, but blind corporate loyalty is poison in a partnership. Yes, you represent your company. Yes, you should defend its interests. But that’s not the same as parroting corporate dogma or being a sycophant for headquarters. Real partnership requires you to show up as a thinking, flexible, honest human being. If you’re just “the company person” who can’t open up, who hides behind talking points, then you can’t build trust. And without trust, the whole thing collapses. So yes, look out for your company—but leave the corporate automaton routine at the door.

In Summary

The theme should be clear by now: lighthouse partnerships don’t rise or fall on the obvious or the political. They succeed because the people involved are self-aware, honest, and trustworthy—and they fail when ego, competitiveness, or blind loyalty creep in. Get that balance right, and the light stays on. Get it wrong, and you’re sailing in the dark.

Narrowing the Lens: Startups and the Lighthouse Partnership

Let’s zero in on startups, because they need partnerships the most.

You’ve got the big idea. You muster the courage to bring it to life. You scrape together some funding—or put in your own money. You start building. You start talking to people just to make sure you’re not crazy. And soon enough, reality sets in: you need customers. Customers bring revenue. Revenue brings freedom. You dream of that hockey stick growth curve, but sooner or later, the dream collides with reality. You need paying customers—or you’ve got nothing.

This is where the lighthouse partnership becomes oxygen. At the revenue crossroads, when you’ve got a product that’s more prototype than finished solution, you need someone willing to take the risk with you. Someone to “invest”—not by writing a check for equity, but by paying real dollars for something half-formed but full of promise. That first customer, that first believer, is a partner. And their decision to join you is what breathes life into your business.

So who are these lighthouse partners? They can take many forms:

An old colleague or former customer who trusts you.

A supplier who sees mutual benefit.

A desperate customer in real pain who is willing to bet on your solution.

No matter where they come from, the role is the same: they are the beacon in the storm, the light guiding you toward safe ground. They’re the ones who say, “I’ll take the risk. I’ll put in dollars, time, and resources. I’ll row the boat with you.” And when they climb into that boat, you both commit to rowing toward the same lighthouse. Because trying to row alone in rough seas almost always ends in capsizing.

And once you’ve found a lighthouse partner willing to row with you—what then?

That’s where the real voyage begins, and where most founders underestimate the grind. Rowing together isn’t just about pulling hard—it’s about rhythm, timing, and agreeing on where the hell you’re headed. Without rules of the water—shared bearings, trusted signals, ways to steer when the tide shifts—you’ll drift off course or worse, spin in circles while exhaustion sets in. Partnerships almost always start with energy and optimism, but energy alone won’t carry you through storms. What separates partnerships that reach the lighthouse from those that capsize isn’t luck—it’s discipline, honest communication, and the courage to row in sync when waves hit. Some lessons came from mentors who had already weathered storms, others I learned the painful way by running aground. Together, they’ve shaped practices that turn a partnership from a gamble into something real—something that gets you to the light.

To make sense of it, I’ve pulled together six key ideas I believe form the backbone of successful lighthouse partnerships. There are plenty of frameworks out there, and I won’t pretend this is all original—because it’s not. Some I lived, some were passed down from mentors, and some borrow from the hard-won work of others who mapped these waters before me. I’ve found the clearest way to organize them is into two categories: Scoping Theories and Growing Theories. Scoping happens before you shove off—prep work, quiet thinking, maps and “what ifs” that help you understand the boat and the crew. Growing is the messy, sweaty, in-motion part of the journey where winds shift and you figure out how to build speed without taking on water. Some ideas are simple, others layered, but together they form a process—not a rigid checklist, but a way to travel. Principles you can carry no matter which harbor you leave or which storm you head into.

The Scoping Theories: Getting the Balloon into the Air

Getting your lighthouse partnership off the ground actually starts before you ever sit at the table. Usually, you’ve got a goal, a hunch, a strategy—or just enough conviction to make you reach out to someone else. And almost always, what you’re looking for is someone willing to put real skin in the game—whether that’s capital, resources, or simply belief in your idea.

That’s where the Scoping Theories come in. They’re part planning exercises, part mindset checks. One of them is a more involved framework, almost diagnostic in nature, that’s incredibly useful for assessing where you stand. The other two are simpler but no less important—they’re lenses that force you to think more broadly than most founders naturally do when approaching a potential lighthouse partner. You can choose to heed them or ignore them, but I’d argue the warning signs they surface are worth your time. So let’s start with one of the best lighthouse partnership planning exercises I’ve ever come across. It looks involved at first glance, but in practice it’s gospel: comprehensive, simple, multifaceted, and deeply valuable.

Larraine Segil's Mindshift Approach taught in Cal Tech Seminar 2003

Before you even begin, there’s a simple but powerful exercise to frame how you should think about a potential partner. I first came across it back in 2003 at an alliance management seminar led by Larraine Segil and Emilio Fontana of the Lared Group. That session taught me many things, but one idea stood out. Segil’s book Intelligent Business Alliances touches on it, but in the seminar, it was taught with real clarity. It’s called the Mindshift Approach to Relationship Development, and it breaks down into three key parts worth considering.

The point of this model is to help you take a step back and think through your partner before you even engage. It isn’t really about them—it’s about you getting clarity around the fit between you and your partner. The model forces you to size yourself up against their interests, so you can anticipate where friction will show up and where things can go awry.

The elegance of this approach is that it asks you to look at three levels: the companies themselves (their corporate personality), the people involved (the day-to-day contacts), and the project itself (what does it mean for you, and what does it mean for them). By breaking these down one by one—which is honestly a fun and eye-opening exercise—you can start to see where danger lurks before you even start. And yes, partnerships are about opportunity, but if we’re honest, there is just as much danger in them as there is promise.

Let’s look at each of the three parts, and then I’ll share an example.

Corporate Personality

This is the most obvious place to start, but also one of the easiest to gloss over. Companies, just like people, have personalities—and those personalities shift depending on where they are in their corporate lifecycle. The spectrum is fairly standard: startup, hockey-stick growth, professionalizing, mature, declining, or sustaining. Each phase comes with its own archetype, its own quirks, its own tempo.

Think about it: the way a scrappy startup makes decisions is radically different from how a mature global corporation does. A startup is all speed, improvisation, and bets on vision. A mature corporation is process-driven, cautious, and slow-moving. A growth-stage “hockey-stick” company might be open to experiments, but its speed can create chaos and resource strain. Each stage dictates not only the pace of business, but also things like decision-making style, risk tolerance, and what financial hurdles look like for success.

This isn’t just a theoretical exercise. It’s critical to map where you sit in your lifecycle and where your potential lighthouse partner sits. That context lets you anticipate the gaps. For example, if you’re a young startup working with a sustaining giant, you know from day one that timelines, budgets, and priorities will move at different speeds. Without realizing this, you’ll constantly get frustrated at the mismatch. With it, you can plan ahead and meet them where they are.

Individual Personality

Even if you’ve sized up the company, you can’t ignore the next layer down: the individuals. Every partnership runs through people—your sponsor, your direct contact, and the broader team on their side. This is the second variable to weigh carefully.

Segil mapped out managerial personalities—hunters, warriors, adventurers, bureaucrats, visionaries, and so on—and these types can make or break your experience. Why? Because your main point of contact might look nothing like the company they represent. You might be dealing with an adventurous, risk-taking sponsor inside a buttoned-up mature corporation. Or you might meet a cautious bureaucrat at a fast-moving startup. Both scenarios create tension.

The key is being aware of who you’re working with and how they operate. People are your guides through the labyrinth of the larger organization, and their personality shapes how much traction you’ll get, how much risk they’ll take, and how fast things will move. Understanding the company’s personality is table stakes, but layering it against the individual personalities involved is where you really start to see the true landscape of the partnership. Ignore this, and you’ll either push too hard in the wrong way—or miss opportunities right in front of you.

Project Personality

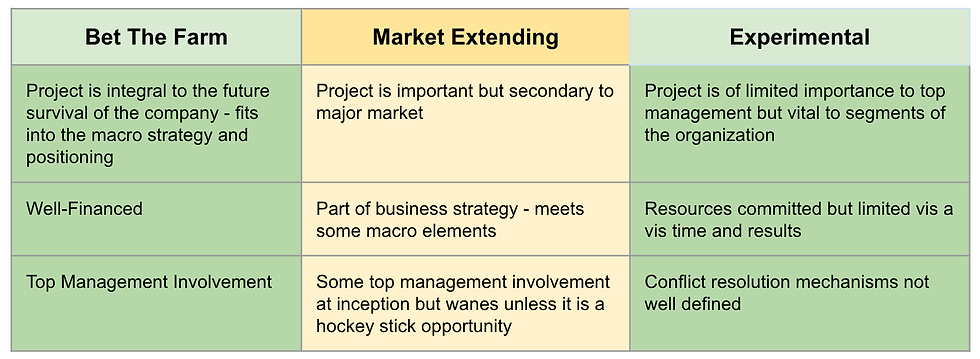

Finally, there’s the project itself—the part most people overlook. Everyone tends to think about the company and the individuals, but they forget to step back and ask: what is this project for each of us?

Segil broke this down into categories like experimental, mission-critical, sustaining, or “bet the farm.” And the insight here is simple but powerful: your project might not mean the same thing to your partner as it does to you.

This is actually the most important lens of the three, and in many ways the simplest. If you’re approaching a partnership thinking this is a “bet the farm” initiative while your partner sees it as an “experiment,” you’re not aligned from the start. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t move forward, but it should tell you to calibrate expectations. On the flip side, if they see the project as mission-critical and you treat it as a side experiment, you’ll let them down.

Personally, I’d start with this one every time. Project alignment sets the tone for everything else. Knowing how you each define the project’s weight and role in your businesses will help you decide whether to push forward, adjust, or walk away entirely.

An Example I Always Remember

When I was at Clorox searching for new technology, I met with a small company that had developed a biodegradable packaging solution. For Clorox, this was purely an experimental R&D project. I was using the Mindshift lens at the time, so I knew exactly how to frame it internally. The company, on the other hand, was a startup, led by executives who were visionaries and adventurers by personality. And for them, this project was “bet the farm.”

They told me proudly that they had been in deep development with McDonald’s for three years, working on packaging that looked a lot like a Big Mac clamshell. Their founder told us this was going to roll out worldwide. And then came the kicker: just three weeks before meeting with us, they’d been told the project was dead. Years of work, millions of dollars, all gone in one conversation. They were devastated, and honestly, doomed.

Why? Because they never applied the Mindshift lens. For McDonald’s, this was an experimental project at best. For them, it was the entire company. Add in the fact that McDonald’s was a mature organization while they were a startup, and that their sponsor was likely an adventurer or visionary type not representative of the larger organization, and the writing was on the wall.

It was my first lesson seeing the Mindshift approach “in the wild.” That company didn’t survive the failure. And it burned into my mind the importance of doing this work up front.

The Mindshift Takeaway

Before you chase a lighthouse partner, you need to pause and assess. Companies, individuals, and projects all come with their own personalities. If you ignore them, you’re flying blind. If you take the time to map them out, you’ll see the danger before you step into it—and that’s the difference between a lighthouse partnership that helps you grow and one that drags you under.

Larraine Segil's: Their Crumbs Your Cake

In this post on lighthouse partnerships, I’ve laid out a number of my own rules of thumb. But some of the most important ones come straight from mentors and teachers who shaped the way I think about partnering. A few, like the Mindshift Approach, require detail. Others are as simple as a sentence.

Back in 2003, in the same class with Larraine Segil, she said something that has stuck with me ever since. It became a kind of mantra I carry into every partnership discussion—a reminder to think a little wider, a little differently, before locking in.

Segil told us the story of how she built a wildly successful business in a brutally crowded market. The giants were everywhere. But when she studied the space, she realized there was daylight—areas the behemoths simply weren’t covering. So she launched what, on the surface, looked like a “been there, done that” business. And it took off.

We were all wide-eyed listening to her. How do you dare take on entrenched players? How do you succeed where they could squash you in a second? Then she gave the line that explained it all:

“Sometimes someone’s crumbs are someone else’s cake.”

That was it. Simple. True. For the behemoth, those opportunities were just crumbs, not worth the effort. But for her, those crumbs were the whole cake—a business big enough to build on and win.

Why bring this up in a post about lighthouse partnerships? Because when your mindshift doesn’t fully line up with your partner’s, the Crumbs/Cake model can be the bridge. What looks small or even irrelevant to one side can be deeply valuable to the other. And if you recognize that dynamic early, you might just uncover a way for everyone to walk away better off—even if it lands you in what I talk about below as Step 3: Joint Gain.

Bishop's Joint Gain Concept: Joint Gain is being real. Win-Win is being hopeful

One of the most useful ideas I ever came across in thinking about partnerships comes from Russell Bishop, who talked about “joint gain.” The concept is simple but powerful: in any partnership, both sides should walk away with more than they could have gotten alone. Not just in theory, not just on paper, but in the lived experience of working together.

The reason this is so important is because most people approach partnering with a “win-win” mentality. That’s what you were probably thinking, right? The problem is that win-win implies I get 50% and you get 50%. Everyone walks away with an equal share. It sounds nice, but in practice it’s almost never true. And yet, if I had a dollar for every time someone said “win-win” when going into a partnership, I wouldn’t still be working.

Joint Gain is different. Bishop defined it as this: sometimes I get 80% and you get 20%, but we’re still both better off than if we hadn’t partnered at all. Why? Because the whole point is that both sides are better off—not equally, but measurably better off—because they came together. That might mean speed to market, credibility in a new category, access to a customer base, or simply the belief that someone else is rowing with you.

This is the subtle but critical shift: partnerships are not about splitting the pie evenly. They’re about making a bigger pie. If you go in expecting fairness measured only by symmetry, you’ll be disappointed. If you go in looking for joint gain—where the math may not look equal, but the outcome is better for both—you’ll find a much stronger foundation for long-term collaboration.

The Growing Theories: Keeping the Balloon in the Air

You’ve scoped, you’ve prepared, and now you’re no longer on shore—you’re in the boat together. For many founders, even reaching this stage feels like a victory worth celebrating. Why? Because in a lighthouse partnership, formality usually means two things: real revenue in your pocket and real validation that your idea is worth betting on. It’s the first deep breath after months (or years) of holding it in, proof that all the sweat and late nights are starting to mean something. Make no mistake—getting someone to formally transact with you is a milestone. It signals your vision is credible enough that another company is willing to invest their dollars, time, or reputation alongside you.

But once that initial champagne moment fades, the real voyage begins. The waters get choppier, the expectations higher, and the stakes sharper. This is where many partnerships sink or stall, not because of a lack of effort, but because founders underestimate what it takes to keep the balloon in the air—or in nautical terms, to keep the boat not just afloat, but moving forward with purpose. That’s why I think of this next set of principles as the Growing Theories. They’re less about the initial handshake and more about how you show up once you’re in motion: how you behave inside the partnership, what habits you lean on, and how you adapt when the wind shifts.

A few of these theories may feel deceptively simple, but as I’ve said before, what’s “obvious” in theory is rarely obvious in practice. Two of them I’ve explored in depth in other posts, so here I’ll only share the topline version and link to the longer dives for anyone who wants the full picture. The point isn’t to hand you a rigid playbook—it’s to give you a set of living guidelines you can actually carry into the boat with you. With that, let’s dig into the Growing Theories.

Robert Porter Lynch and Paul Lawrence’s Trust Ladder: Trust as Both Fuel and Grease

For those who don’t know him (and odds are, you don’t), Robert Porter Lynch is one of the godfathers of alliance management—and I’m lucky to call him not just a mentor, but a thought partner and friend. Years ago, he flat-out told me something no one else had the guts to say: the job I was in was killing me, because they were never going to see the world the way I did. He was right. His guidance gave me the courage to jump ship, step out of the grind, and begin walking the road toward innovation and evangelism.

Writing this section—like I did earlier with Segil—is my way of paying homage to the people who fundamentally reshaped how I think about partnerships. Because if there’s a centerpiece to understanding how real partnering works, it’s Lynch and Lawrence’s concept of the Trust Ladder. Hardly anyone knows about it, but in my view, it’s one of the most powerful models for shifting your mindset about collaboration. At its core, it frames trust not as some soft, fuzzy ideal, but as both the fuel that propels a partnership forward and the grease that keeps the gears from grinding when friction inevitably shows up.

Now, Lynch and Lawrence anchor their work around two critical models. The first focuses on the behavior drivers of leaders—what truly motivates people when they step into the arena of partnership. It’s simple, elegant, and sharp enough that there’s no reason for me to paraphrase. Instead, I’ll drop their original graphic and a direct excerpt from their article here, because sometimes the clearest thing you can do is just point to the source.

Here’s their breakdown of the chart. They go much deeper in the full article—and I’ll share the link at the end if you want to dive in—but for the purpose of the Growing Theories, these are the models that matter most. Think of them as a mirror: tools to assess not just your own behavior, but also the people sitting across the table in your partnership.

• Drive to Acquire – to compete for, secure, and own at least a minimum of essential resources (food, shelter, mate, etc.), to exert sufficient control over one’s environment for this purpose, and, when pushed by desperation into greed and domination.

• Drive to Bond – to form long-term mutually caring relationships, to cooperate with others, engage in teams, build organizations and alliances, and, at its fullest, to put moral meaning in all relationships.

• Drive to Create – first to learn, to comprehend one’s self and environment, then to inquire beyond, and most fully, to imagine and invent.

• Drive to Defend – to protect from threats to one’s physical self and loved ones, to have security and safety of one’s valued possessions and basic beliefs, and, pushed to the extreme: to attack.4

This model gives anyone in a lighthouse partnership a way to gauge where their team is “living.” You can watch these behaviors play out in your counterparts, and like it or not, their behavior will dictate how they choose to bring trust—or not bring it—into your shared effort. Most of the time, the heartbeat of a lighthouse partnership is the drive to create and bond. But we’ve all seen partnerships go sideways when the other three leadership styles creep in and start driving the interaction. The key is awareness: spot these behaviors early and guard against them infiltrating your work. Because when you find partners who truly want to bond and create, you’ve set the stage for the next critical layer of Lynch and Lawrence’s theory—the kind of partnership you’ll actually build into your lighthouse journey.

The Trust Ladder: a model of pure partnership clarity

The crown jewel of their work is the concept of the Trust Ladder. Like the best frameworks, it’s simple, portable, and endlessly adaptable—it works anytime, anywhere, no matter how you slice it. That’s the power of the Trust Ladder. And below is their model to start framing your own thinking.

You’ll quickly notice this model takes the four quadrants of leadership from the first chart and overlays what Lynch and Lawrence call the Trust Ladder. And if you sit with it for a moment, it really can open your mind in ways you might not expect. Their breakthrough is this: trust isn’t a binary yes/no switch. It isn’t simply a matter of “I trust you” or “I don’t.” Instead, they take us to an entirely new place by asking the deeper question: how do you trust someone?

They show that trust has gradations—shades of both positive and negative—and we live somewhere on that ladder at any given time. That’s the genius of this model. Any interaction can begin at any rung and then either climb toward greater positive trust or slide downward into negative trust. Even more powerful, they define the rungs themselves, giving us a dynamic and well-structured way to talk about what’s often an invisible, slippery concept.

If you want the full detail, I’ll link the original article at the end of this section. For now, let’s highlight the parts most relevant to lighthouse partnering.

Starting in the Neutral Middle: The Transaction

The clearest place to begin with the Trust Ladder is in the middle: the transaction. This is neutral trust. Nothing more, nothing less. Two parties exchange goods or services—I hand over money, you hand over the product, and off we go. It’s a daily ritual we rarely stop to think about, but Lynch and Lawrence point out something profound here: even a transaction rests on trust.

When you buy gum at a store, you trust the gum will be what you expect, and the cashier trusts your money will be good. That’s neutral trust: not positive, not negative, just the baseline expectation of fair exchange. While this state isn’t where lighthouse partnerships live, it highlights something critical—trust is present in every relationship, whether we see it or not. Knowing this makes us more mindful of the levels of trust we’re building, and more importantly, whether we’re raising that level or allowing it to slip in the wrong direction.

The Place We Never Want to Go: Down the Negative Trust Ladder

Now, let’s talk about the darker side: negative trust. This is where partnerships collapse. This is the “one day everything seems fine, the next day the wheels come off” scenario. But the beauty of the model is that it gives us a way to spot the descent before it’s too late.

Negative trust isn’t a sudden event; it’s usually a slow slide. Lynch and Lawrence outline stages—negativity, denial, manipulation, deception, aggression, and even character assassination. Each stage has behaviors you can identify in your counterpart, in their leadership, or even on your own team. Once those behaviors appear, the slope steepens, and negative trust spreads like a virus.

This is why the Trust Ladder matters so much for lighthouse partnering: it gives us operational definitions of what negative trust looks like. Being forewarned means you can recognize the signs early, take action, and protect the partnership before it fractures beyond repair.

The Place We Want to Exist: Up the Positive Trust Ladder

People tend to believe they’ll always live on the higher rungs of trust—and it’s a good goal—but most don’t truly grasp the nuances of positive trust. If you want to walk all the way up the ladder, I’d suggest reading the original article by Lynch and Lawrence. Their work shines a light on the subtle differences between each step as you move from the neutral state of transactional trust, up through relationship, guardianship, companionship, friendship, partnership, and ultimately to what might be the greatest word ever created for innovation-focused business: creationship (their invented term).

For lighthouse partnering, I focus on just two of these states—partnership and creationship. I do this intentionally, because they highlight the gap between what most of us operationally define as “success” and what we’re actually striving toward. From the first moment Robert Porter Lynch shared the idea of a creationship with me, I was hooked. Its brilliance lies in how it reframes collaboration into something that transcends business jargon—simple, logical, and yet incredibly difficult to achieve without an operational definition to aim for. Rather than paraphrase, I’ll let Lynch and Lawrence’s own words speak for themselves before unpacking what they mean in the context of Growing and lighthouse partnerships.

The Definition of Partnership (by Lynch and Lawrence)

"A partnership is designed to respect and cherish the differences in thinking and capabilities between two or more people or organizations. It is the combination of differing strengths with the alignment of a common purpose that makes a partnership effective. For example, one person does outside sales, another keeps the finances on track, while another runs operations. Great partnering relationships require a number of things to make them work effectively:

Shared Vision: Trust is built by the power of the commitment to a shared view of the unfolding future. While making today’s dollar is essential in any business, great partnerships are always looking one step ahead to find the new opportunity, to design the future, to turn adversity to advantage.

Shared Planning: People support what they help create. This builds trust because those thus engaged are consulted and their ideas are valued, which, in turn builds even stronger commitment to the future.

Shared Resources, Risks and Rewards: By sharing risk and reward, people have “skin in the game.” The more everyone shares risks and rewards, the more powerful the level of commitment."

The Definition of Creationship (by Lynch and Lawrence)

"For this level of trust we had to create a new word. A “creationship” implies that we can do something extraordinary – we can co-create together. A creationship embraces prior elements of trust-building, and then, secure in the absence of fear, unleashes a connection between the hearts and minds of the co-creators – new ideas generate like spontaneous combustion.

How does the leader foster creationships? Here are some ways:

Purpose and Destiny: Some of the most co-creative people on the planet are those with a deep central sense of personal purpose or destiny. This kind of purpose gives meaning and value to whatever we do – there is a reason for being and doing in our daily lives.

No such thing as Failure, Only Learning: Be careful not to punish what might look like a failed attempt at creative solutions. Be sure to encourage learning from failures. Remember, high performance teams fail more often than low performance teams; the difference is how they learn — then innovate from what they learned.

Use Conflict to Advantage: Whenever there’s change, conflict is inevitable as systems, strategies, roles, and perspectives shift, even in a trusting environment. Don’t shove conflict under the rug, but use it as a learning mechanism. Focus on shifting perspectives; prevent people from becoming entrenched in one point of view.

Laugh! Creationship teams are not all grinding labor; it’s having fun with what they do and laughing a lot, spontaneously creating in the moment – that’s magical. Research shows that laughter releases endorphins that trigger creativity. Laughter expresses the absence of fear."

Digging Deeper Into Higher States of Trust

There’s nothing wrong with a trusted lighthouse partnership—it’s a high state of trust in its own right. A true partnership blends differences, aligns vision, and commits to shared resources, planning, and risks. That’s a winning formula, and if every lighthouse partnership could hold that level of trust without slipping downward into negative trust, you’d have more than enough fuel to drive toward value. But here’s the question: when you’re building a business, pioneering a market, or breaking conventions, is partnership alone really enough?

That’s where the creationship enters. Once you’ve been awakened to the possibility of this higher state, partnership—even at its best—can start to feel sterile. Creationships are seamless, almost enlightened collaborations where fear is absent, learning is constant, and shared purpose drives effortless execution. Since first discovering this concept, I’ve looked for partners who operate at this level—those rare innovation kindred spirits who make success feel natural, sustainable, and long-term. That awareness was a turning point in how I approached every collaboration.

How to Spot a Creationship

You find innovation kindred spirits. Some people just feel in sync with you from the start. Trust your gut—when someone’s innovation rhythm complements your own, that’s a signal you may have found a creationship. One clue is that it doesn’t feel like work.

The collaboration is a force multiplier. From the beginning, you can tell that working together will create exponential value. It’s bigger than joint gain or even win-win—it’s a level where you’d be foolish not to lean in fully.

The personal connection forms without effort. Sometimes strangers feel like old friends. That eerie but natural connection isn’t creepy—it’s collaborative magic. Embrace it, explore it, and keep your mind open. Sometimes the partnerships that feel “too good to be true” are actually the ones pointing you toward a creationship.

If you want to grow a budding partnership, you have to commit to real engagement. The Trust Ladder gives you that framework. It takes what we instinctively know about trust and puts it into a model we can actually use as we work alongside a lighthouse partner.

The Team within a Team concept of partnering

As the owner of many innovation partnerships, you start to pick up patterns about what actually drives success. One of my biggest learnings is the team within a team concept. Think of it as the Growing Theory sibling to the MindShift Approach. Why? Because the MindShift Approach is all about preparing yourself and your organization for the partnership—it’s the pregame work, the mindset shift, the setup. But the team within a team is different. It’s what happens after the partnership is formed. It’s about how you behave once you’re in the boat together and rowing toward the lighthouse.

In that way, the team within a team becomes a critical behavioral theory for making a lighthouse partnership thrive. It’s not just about launching; it’s about learning how to operate. It’s the playbook for how to move in sync, how to trust, and how to keep the shared engine running. Before we dig into it, let’s first re-define what an innovation partnership actually is (yes, again—but this time in the context of execution). Then we can look at how a partnership evolves, and more importantly, how systematic behavior transforms it into something greater: a creationship.

My definition of an innovation partnership: A collaboration between groups of people working across either inter-company boundaries (different business units, functions, geographies, or groups) or intra-company boundaries (two different corporate or government entities) to produce a novel innovation. When talking about subjects like this, it’s critical to align on operational definitions so we can change behavior in the context of a defined thing and minimize disconnect. And yes—everything here sits on top of the Trust Ladder and the lighthouse mindset we’ve been building: trust as fuel and grease, rowing in rhythm toward the light.

Laying out the partnership players, roles, and structureThis one’s simple. In any inter-company partnership there are layers, and each layer has its own interests:

The Company (The Entity). Both sides answer to a company—policy, rules, and culture included. In innovation work, the company is the silent guide between parties and absolutely influences whether collaboration happens or stalls.

Senior Management (The Coverage). The execs (VP and above) who sanction the work and make the final calls. They’re not in the day-to-day, but their blessing (or intervention) is always in the back of everyone’s mind—especially when non-sponsoring execs try to “use the company” to stop change. Partnerships can start top-down or bottom-up; in bottoms-up, senior leaders may not show up until the first win goes public.

Middle Management (The Stakeholders). Love them or hate them, they provide air cover and also get the glory. Their incentive is to ship something that changes how the company operates, makes money, or saves money. They’ll help craft and guide—and they can also deny you. Your success depends on a few things:

Will they provide true air cover, or bolt at the first sign of trouble?

Will they let the team scope the work, or over-manage from the sidelines?

Can you keep both sides’ middle managers aligned, even under pressure from their own orgs?

The Team (The Engine). The people at the interface. Their job is to represent their companies’ interests, set timelines, goals, and metrics—and get the collaboration across the line. The real question: how will two separate engines merge to drive the car to the finish line?

What is the “team within a team”… and what makes partnerships work?

The team within a team strips out the cultural barriers so it doesn’t feel like work. It’s implicit trust, open communication, and cultural transparency that signal commitment to the partnership’s goal above each company’s instinct to “company up.”

What it feels like when it’s working

It doesn’t seem like work. The people make sense. The work makes sense. The process makes sense. Mature behavior, clean communication lines, and a functional system on both sides. It clicks.

You don’t let corporate culture rule you. Culture enables execution and creates groupthink. It gives people a way to fail “appropriately,” and it arms robots to weaponize process. Leave that pull at the door when two cultures meet, or entropy eats innovation.

You put friendship before business. Bass-ackwards, sure—but it builds loyalty and trust that won’t break when the seas get rough. Know each other beyond the project. When trouble brews, friendship helps you solve problems without burning the boat.

Rules of thumb inside the bubble

Friendship first, business second. Trust compounds in small moments—late calls taken, cover given, info shared.

Be honest about weaknesses and culture. Say the quiet parts out loud: how your org decides, where it drags, what it won’t do. Make culture tangible so you can route around it—or use it.

Crawl, walk, run. Start with a small, protected win to show what’s possible, map the walk, then the run. Momentum beats theater.

Fight “company up.” When fear hits and someone retreats to the logo, cracks appear. Hold the line together.

The evolved partnership state

This is the first stage of building a team within a team to break the company-interest barrier anywhere you can—ideally at the key interface: the team. Open-minded means breaking from your corporate reflexes, resisting fear, and sometimes doing what’s best for the partnership over what’s safest inside your org. It means trusting counterparts implicitly and being candid about where your company slows or blocks progress. In the evolved state, you may only break the culture barrier at the team layer—and that’s often enough to win, as long as no one panics and “companies up.”

A quick example + resultsI was dropped into a busted alliance between two mega-orgs—Company A (my side, the customer) and Company B (the supplier). We reset the team at the interface and did three things:

Laid out interests clearly and transparently (“no secrets,” loyalty to the shared work, not just the logo).

Talked openly about culture on both sides—how decisions actually get made, what won’t fly, and how to leverage both cultures to drive change.

Agreed to a crawl / walk / run path—prove value small, then scale.

What happened:

Ran a 4-day inter-company offsite with 60+ people and built a real pipeline.

Drove $150M+ in new products across multiple business units.

Shifted from evolved to enlightened—corporate lines blurred across teams, managers, leadership.

Years later, I can still pick up the phone and pitch anyone from that team.

The enlightened partnership state

An enlightened innovation partnership creates its own mass between the two companies—a cross-company bubble of collaboration born from a level of inter-company trust that rarely exists. It takes the team within a team and expands it across the entire partnership infrastructure. It’s rarified air; people talk about it, few achieve it. Reorgs, role changes, shifting priorities—those will happen. The test is whether your bubble survives the weather.

Why it’s resilient

The partnership becomes its own entity. The “new innovation culture” absorbs change; new players must adapt to it, not the other way around. No single change is bigger than the shared goal.

People want in. Success, fun, and momentum attract talent. When folks fight to join the team, continuity follows.

People get promoted into power. Wins move people up. They carry the playbook, expand authority, and keep decisions aligned with the partnership’s true north.

Bringing it home

The road to a successful innovation partnership is long and winding. It won’t always happen. The best shot is to build structures that point to where you want to go, then lead people there—evangelist-style. The seeds start with how you behave at the transom between two orgs. It flourishes when others believe. It grows when you make the team within a team real at that interface. Start there. Make it infectious. Magical things can happen. “Company up,” and you’ll get the same stale outcome you’ve always gotten. It’s up to you.

—Want the full blog post with the drawings, deeper context, and the whole story? Read it here: https://www.innovationmuse.io/post/innovation-partnerships-the-team-within-a-team

Alliances: As They Grow, They Wither

So you’ve planned and prepared. You’ve thought carefully about your lighthouse partnership. You understand how to build positive trust and spot the bad trust juju. You stood it up and built a tight team that rows in rhythm. That’s it, right? Nope. Once your core team starts stacking wins, the old saying kicks in: success has many parents and failure is an orphan. If you’ve made it here, the real danger begins. After 30 years running the transom between big and small, I’ve learned a hard truth: as alliances grow, they wither.

What does this mean? A concrete read

As the number of people involved in a lighthouse partnership/strategic alliance grows, all else equal, the overall health of that partnership naturally declines. More bodies, more gravity. The system gets heavier.

Why is this important?

Everything we’ve talked about in building a lighthouse partnership centers around culture, trust, people, and how to create a seamless working relationship. If you believe those are the core ingredients of success, then you also need to accept this truth: more people means more personalities, more interests, more egos, more self-interest, and ultimately, more problems.

This doesn’t guarantee failure. But like most things in this long and winding discussion, you need to understand that success doesn’t make partnerships easier—it actually makes them harder. When you’re flying high with that team within a team, building your first wins, that’s the moment to keep your eyes wide open. Growth brings risk, and you won’t always control who gets added to the mix. Lighthouse partnerships are complex systems. Knowing that there’s downward pressure on health as they grow allows you to prepare for it before it knocks you off balance.

A true story: from $0 → $5MM → $0 (again)

One of my first lighthouse partnerships was also one of my most successful—and most instructive. Early in my career, I stumbled on a novel way to use an old technology from an even older supplier. They’d been in our building a thousand times, never got much business, but kept trying to break in. I decided to own the relationship. I mocked up prototypes, shaped the concept, and sold it internally. Marketing liked it enough to license the supplier’s brand, which meant we needed a joint development agreement (my first—I had no idea what I was doing), and somehow we got it signed.

Fast-forward ~2 years: we launched a product platform that did $50–70MM, cracked a category we could never enter, and worked with five other companies to bolt on additional tech. By consumer-product standards, that’s a win. Our team within a team ran on complete trust to get it airborne. And while the commodity volume with that supplier was small at first, we had a principle we called win balancing: if you innovate with us, we’ll steer more commodity business your way to reward the risk. Because the partnership became a creationship, the supplier went from $0 to $5MM with us. Great story… until it wasn’t.

My day-to-day counterpart—fresh off that win—got moved. New contacts came in. Different vibe; they didn’t get it. Their executive stakeholders shifted too. Meanwhile, people inside my company wanted a piece, spun up side projects, and piled on with those new leaders. More bodies, more noise. I got reassigned. Within 18 months: trust eroded, incentives misaligned, chaos set in. The whole thing collapsed back to $0. I’m skipping a lot of drama, but the lesson is clear: even in an “ideal” partnership, as people rotate in and crowd the field, the sanctity of the original construct slips into the danger zone. Downward pressure is real. You have to manage it.

What Can You Do?

Thought 1: Engage leadership quickly

Leadership needs to understand this principle: the health of any partnership is inversely related to unchecked growth. Don’t assume they see it—make them see it. If you are the keeper of the lighthouse partnership, it’s your responsibility to educate, frame the risk, and show how success can plant the seeds of its own undoing. Engaged leadership can help you shield the partnership from unnecessary noise, allocate resources wisely, and defend its culture.

Thought 2: Work to bring the right people in

If growth creates risk, then you must be deliberate about who gets added. Every new person should be additive, not corrosive. Don’t allow new voices to set the cultural tone—curate them. Look for people who align with the trust, values, and operating style already in place. Even small misalignments can accelerate the downward pressure. Treat each new addition as a critical hire for your partnership’s survival.

Thought 3: Own the issue

This one is non-negotiable: you own it. Don’t ever assume a successful partnership can run on autopilot. Keep scanning for cracks, keep working the trust levers, and keep resetting the system when needed. Partnerships are living things. They can last years, but only if you actively monitor and reapply the principles that built them in the first place. When the danger signs appear, don’t freeze—restart. Pull out the MindShift Approach again. Reassess using the Trust Ladder. Reframe the team within a team. These tools exist so you can respond when complexity threatens to overrun the core.

Wrapping it all up: Apologies, but this shit is complicated

This post is way too long, but the point is actually simple: Lighthouse Partnerships are essential to innovating. They are a must-have tool in your toolbox. Yet so many fail because they tout collaboration, innovation, and partnership—but they focus on what’s not important. At the end of the day, companies don’t innovate. People do.

That’s why I’ve shared these Scoping and Growing Theories and the rules of thumb that come with them. They aren’t abstract frameworks. They are practical lenses you can use to plan, launch, grow, and manage a lighthouse partnership—and avoid the pitfalls that will inevitably show up once the partnership finds some success.

If you’ve noticed, I’ve prioritized people, culture, trust, and connectivity over output, metrics, and function. Don’t get me wrong—those are must-haves. But they aren’t where the danger lies. The danger lies in forgetting that as partnerships grow, their health comes under pressure. The danger lies in losing the team within a team that made it work in the first place. And the danger lies in assuming a partnership can scale without constant care and ownership.

The good news? You can manage this. The rules of thumb outlined here are designed to help you reset, restart, and reframe when complexity creeps in. They’re reminders that innovation partnerships are not static—they’re living systems that need to be tended.

My encouragement to you: use this structure to design your own rules of thumb. Study the dynamics, learn from the warning signs, and commit to being a student of the game.

Lighthouse partnerships take passion and belief to make them synergistic. To row perfectly together, you must commit to the people, the trust, and the culture as much as the output.

God Speed. Good Luck. And may your lighthouse partnerships not just shine, but last.

Comments